That's a Lot of Fish: PlaidCTF 2020

TL;DR

- Reversing; 400 points, 9 solves

- Typing the Techical Interview in TypeScript, with gate-level bitwise arithmetic and a VM on top.

- Jane Street plz hire me

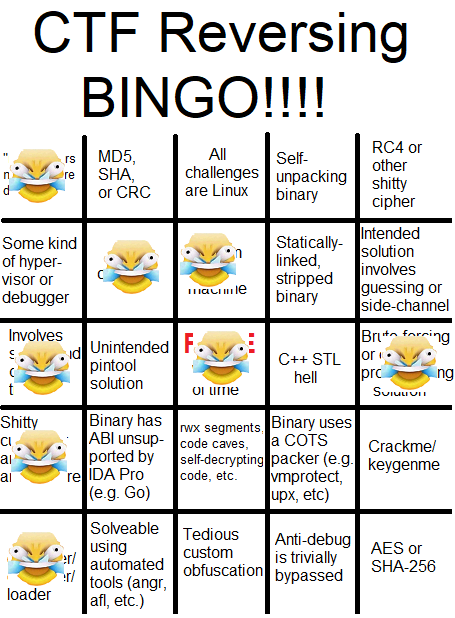

Reversing Bingo board

Rating: 4/5 not quite Bingo but close. Template

Challenge Description

There’s something that looks like Godzilla attacking a skyscraper, but it seems to be made completely of metal. Mechagodzilla? And the military force you followed here doesn’t seem to have a whole lot of weapons. Instead, from the vehicles, you see them unload tons upon tons of fresh fish, amassing them into one giant heap in the middle of the road. Are they trying to distract a mechanical monster with food? That doesn’t sound like a great plan to you. An onlooker beside you that you hadn’t noticed up to this point suddenly pipes up. “That’s a lot of fish,” he states flatly. He’s not wrong, you suppose. As you watch on, for just a moment, you see a corner of a flag sticking out of the pile of fish, before being covered up by some cod and salmon that are added to the top of the pile. Well, it’s not like you have a better option, right? You run up to the smelly pile and plunge in your hands, desperately hoping to locate that flag you just saw.

Overview

That's a Lot of Fish was a PlaidCTF challenge I (cts) particularly enjoyed. It took extremely long, and there are a few cool things I’d like to highlight about it. The challenge itself is relatively straightforward, but does require some brainpower.

Opening the challenge, we’re greeted by the following diff for the Typescript interpreter:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

diff --git a/lib/tsc.js b/lib/tsc.js

index 1a32bce669..aa0a1ede43 100644

--- a/lib/tsc.js

+++ b/lib/tsc.js

@@ -38635,7 +38635,7 @@ var ts;

if (!type || !mapper || mapper === identityMapper) {

return type;

}

- if (instantiationDepth === 50 || instantiationCount >= 5000000) {

+ if (instantiationDepth === 50000 || instantiationCount >= 5000000000) {

error(currentNode, ts.Diagnostics.Type_instantiation_is_excessively_deep_and_possibly_infinite);

return errorType;

}

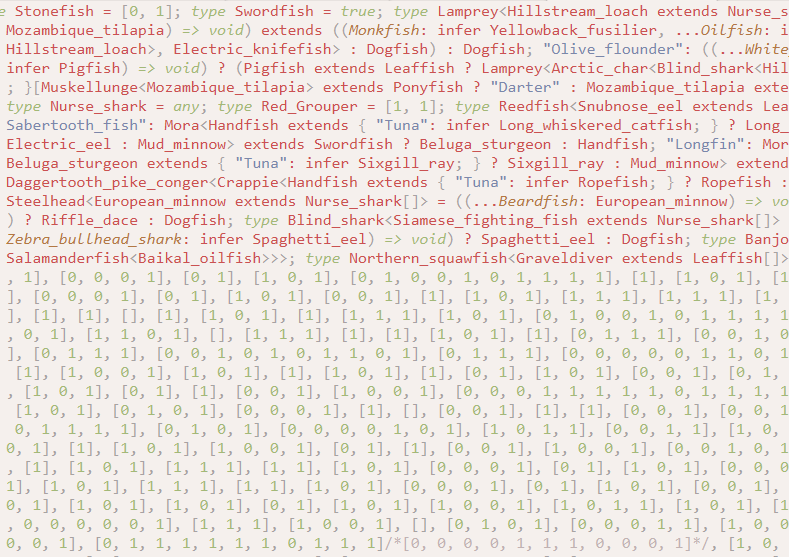

This is… not promising. It seems like they’re forcibly increasing the recursion depth limit. Let’s take a look at the actual source code we’re asked to reverse:

Okay… let’s at least split things up into lines.

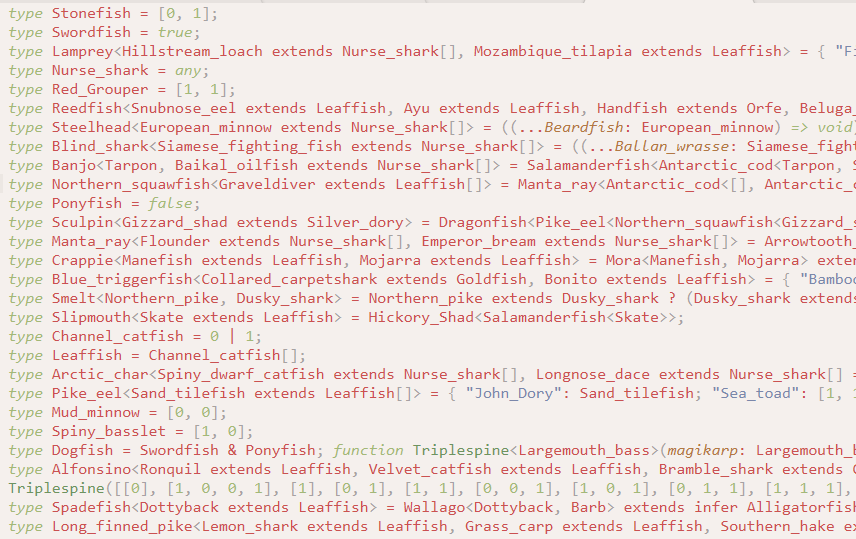

Okay, now this is at least comprehensible…sorta. From first glance, it looks like everything is just a type declaration, including all the constants, the logic, and so on. I have a feeling that this is going to be a type metaprogramming challenge. Since there’s only one declaration per line, let’s sort the lines by length: better to start with the smallest, most comprehensible bits first.

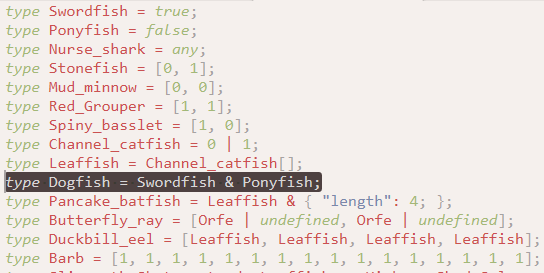

Now we’re getting somewhere! And we have an idea of how they are going to be performing logic. To us, Swordfish is going to be our boolean constant True, Ponyfish is False, and so on. It also seems like Dogfish is an algebraic type that must satisfy both True and False; e.g., the null type never. Let’s double-check our assumptions in a TypeScript REPL:

1

2

3

4

5

> let x: Swordfish = false;

error TS2322: Type 'false' is not assignable to type 'true'.

> let x: Dogfish = 12345;

error TS2322: Type '12345' is not assignable to type 'never'.

Sweet. So it seems like these types essentially constrain what stuff can be assigned; by doing higher-order computations over types, we can end up with a set of constraints that effectively amount to arbitrary computation. In other words, we’re abusing the Turing-completeness of TypeScript’s powerful type system to implement (what I’m guessing will probably be) a flag checker. Let’s start working through the most simple declarations and start renaming our types. Types that are all names of fish.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

type True = true;

type False = false;

type Any = any;

type Never = True & False;

type Binary = 0 | 1; // this type can be integers 0 or 1

type BinNum = Binary[]; // array of integers 0 or 1

type Bin4 = BinNum & { "length": 4; }; // array of 4 integers, 0 or 1

Uh oh. This does not bode well. I have a feeling I know where they’re going with this one. First however, we need to reverse a few primitive functions that are used everywhere else. First, we can check for equality using extends:

1

type Equ<X, Y> = X extends Y ? (Y extends X ? True : False) : False;

1

2

type Cdr<x extends Any[]> = ((...args: x) => void) extends ((arg1: infer First, ...args: infer Tail) => void) ? Tail : Never;

type Car<x extends Any[]> = ((...args: x) => void) extends ((arg1: infer First, ...args: infer Tail) => void) ? First : Never;

Anyone who’s programmed Lisp knows what Cdr and Car do. In short, Car returns the first element of a list, and Cdr returns the rest of the elements. The way they’re implemented here is extremely clever: it’s doing pattern matching on the arguments of some dummy function type. It’s peeling off the first argument of a “…” expansion, similar to Python star-args (*args). Anyways, you can use Car and Cdr with tail recursion to accomplish iteration:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

type EqNum<X extends BinNum, Y extends BinNum> = {

"False": False; // base-case

"Cmp":

X[0] extends Y[0] ? (

Y[0] extends X[0] ?

EqNum<Cdr<X>, Cdr<Y>> // pop off a bit, keep comparing

:

False // the bits are not equal, stop.

) :

False;

"XZero": EqNum<[0], Y>; // Ran out of bits in X, zero-extend with 0s

"YZero": EqNum<X, [0]>; // Ran out of bits in Y, zero-extend with 0s

"True": True; // base-case

}[

IsConcrete<X> extends False ? // error handling, you can ignore this

"False"

: IsConcrete<Y> extends False ?

"False"

: X extends [] ? (

Y extends [] ?

"True" // none of the bits are inequal; the two numbers are equal

:

"XZero"

)

: Y extends [] ?

"YZero"

: "Cmp"

];

There’s a lot to take in here. First, It creates a dict and then indexes into it, as a form of control-flow while preserving tail recursion. It’s kind of like a switch statement. The dict part is responsible for recursing, or returning the base case. The index part does the combinational logic for selecting how to proceed based on the current level.

Second, our BinNums are essentially representations of integers in binary form, with LSB at the front of the array and MSB at the end. So this “function” takes in two BinNums, and returns if they are equal by iterating through the bits in order and checking if they are all equal. Keep in mind everything is actually a type: our functions are conditional types, our parameters are actually type parameters, our numbers are actually just types representing arrays of binary digits. To make this concrete, let me give an example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

type Const_Five = [1,0,1]

type Const_Ten = [0,1,0,1]

let x: Const_Five = [] // What's Const_Five?

// error TS2739: Type '[]' is missing the following properties from type '[1, 0, 1]': 0, 1, 2

let x: Const_Ten = [] // What's Const_Ten?

// error TS2739: Type '[]' is missing the following properties from type '[0, 1, 0, 1]': 0, 1, 2, 3

let x: Add<Const_Five,Const_Five> = [] // What's Add<Const_Five, Const_Five> ?

// error TS2739: Type '[]' is missing the following properties from type '[0, 1, 0, 1]': 0, 1, 2, 3

let x: EqNum<Add<Const_Five,Const_Five>,Const_Ten> = 0; // Is 5+5=10 ?

// error TS2322: Type '0' is not assignable to type 'true'.

let x: EqNum<Add<Const_Five,Const_Five>,Const_Ten> = true; // So 5+5=10.

// [no error]

Now you might be wondering…how do I add two of these binary numbers by (ab)using the type system? Using an adder of course…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

// 2x2x2x2 tensor : in (x,y,state) , out (output,nextState)

// This is a 2-bit full adder truth table. The state is the carry bit.

// y[i]=0 y[i]=1

type FSMTable = [[[[0, 0], [1, 0]], [[1, 0], [0, 1]]], // x[i] = 0

[[[1, 0], [0, 1]], [[0, 1], [1, 1]]]]; // x[i] = 1

// Basic ripple-carry adder

type Add<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum, accum extends Binary = 0, result extends BinNum = []> = {

"Never": Never;

"Next":

FSMTable[Car<x>][Car<y>][accum] extends [infer tensorOut0, infer tensorOut1] ? (

tensorOut1 extends Binary ?

Add<Cdr<x>, Cdr<y>, tensorOut1, ConsEnd<tensorOut0, result>>

:

Never

) :

Never;

"XEmpty": Add<[0], y, accum, result>;

"YEmpty": Add<x, [0], accum, result>;

"Base": accum extends 0 ? result : ConsEnd<accum, result>;

}[

IsConcrete<x> extends False ?

"Never"

: IsConcrete<y> extends False ?

"Never"

: x extends [] ? (

y extends [] ?

"Base"

:

"XEmpty"

) : y extends [] ?

"YEmpty"

:

"Next"

];

Impressed now? Well, I guess it would be nice to be able to do bitwise arithmetic too…shouldn’t be hard right? :)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

type BinaryBitwiseOp<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum, truthtable extends [[Binary, Binary], [Binary, Binary]], result extends BinNum = []> = {

"Never": Never;

"Next": BinaryBitwiseOp<Cdr<x>, Cdr<y>, truthtable, ConsEnd<truthtable[Car<x>][Car<y>], result>>;

"XEmpty": BinaryBitwiseOp<[0], y, truthtable, result>;

"YEmpty": BinaryBitwiseOp<x, [0], truthtable, result>;

"Base": result;

}[

IsConcrete<x> extends False ?

"Never"

: IsConcrete<y> extends False ?

"Never"

: x extends [] ? (

y extends [] ?

"Base"

:

"XEmpty"

)

: y extends [] ?

"YEmpty"

:

"Next"

];

type BitwiseAnd<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum> = BinaryBitwiseOp<x, y, [[0, 0], [0, 1]]>;

type BitwiseOr<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum> = BinaryBitwiseOp<x, y, [[0, 1], [1, 1]]>;

type BitwiseNotXor<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum> = BinaryBitwiseOp<x, y, [[1, 0], [0, 1]]>;

type BitwiseXor<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum> = BinaryBitwiseOp<x, y, [[0, 1], [1, 0]]>;

Or even a multiplier!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

type Multiply<x extends BinNum, y extends BinNum, result extends BinNum = []> = {

"Error": Never;

"XZero": Multiply<Cdr<x>, Cons<0, y>, result>;

"XOne": Multiply<Cdr<x>, Cons<0, y>, Add<y, result>>;

"Base": result;

}[

IsConcrete<x> extends False ?

"Error"

: x extends [] ?

"Base"

: x[0] extends 0 ?

"XZero"

: "XOne"

];

Lastly, there is this awesome trick they used to index into a list by recursively skipping every other element based on the bits of the index.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

// example : let ab : Arctic_char<[1,2,3,4]> = [1, 3]

type EveryOther<X extends Any[], Y extends Any[] = []> = {

"RetY": Y;

"Recursive": ((...args: X) => void) extends ((arg1: infer First, arg2: infer Second, ...rest: infer Tail) => void) ?

EveryOther<Tail, ConsEnd<First, Y>>

: ((...args: X) => void) extends ((arg1: infer First, ...rest: infer Empty) => void) ?

ConsEnd<First, Y>

: Never;

"Error": Never;

}[IsConcrete<X> extends False ?

"Error"

: [] extends X ?

"RetY"

: "Recursive"];

type Index<X extends Any[], Num extends BinNum> = {

"False": ((...args: Num) => void) extends ((arg1: infer Yellowback_fusilier, ...tail: infer Rest) => void) ?

(Rest extends BinNum ?

Index<EveryOther<X>, Rest>

: Never)

: Never;

"True": ((...args: Num) => void) extends ((arg1: infer Fangtooth, ...args: infer Rest) => void) ?

(Rest extends BinNum ?

Index<EveryOther<Cdr<X>>, Rest>

: Never)

: Never;

"Base": X[0];

"Error": Never;

}[IsConcrete<Num> extends False ?

"Error"

: Num extends [] ?

"Base"

: Num[0] extends 0 ?

"False"

: "True"];

Keep in mind, all of these identifiers and strings were just names of fish. So I spent Saturday night discovering how Tuna is actually a ripple-carry adder. Up to this point, I felt pretty smart about myself…until I saw this and my heart sank.

1

2

3

4

type GetSrcOperand<S extends VMState, x extends BinNum> = [ // 2x2 array. operand mode

[Cdr<Cdr<x>>, /* immediate */ Index<S["RegisterFile"], Cdr<Cdr<x>>> /* register value */ ],

[Index<S["TextMem"], Cdr<Cdr<x>>>, /* indirect immediate */ Index<S["TextMem"], Index<S["RegisterFile"], Cdr<Cdr<x>>>> /* indirect register */ ]

][CoerceNumber<Index<x, [1]>>][CoerceNumber<Index<x, [] >>];

I saw this, and I immediately realized that this must be part of some kind of instruction decode. I got this hypothesis because typically RISC processors fetches operands in ID/RR. And just a few lines below:

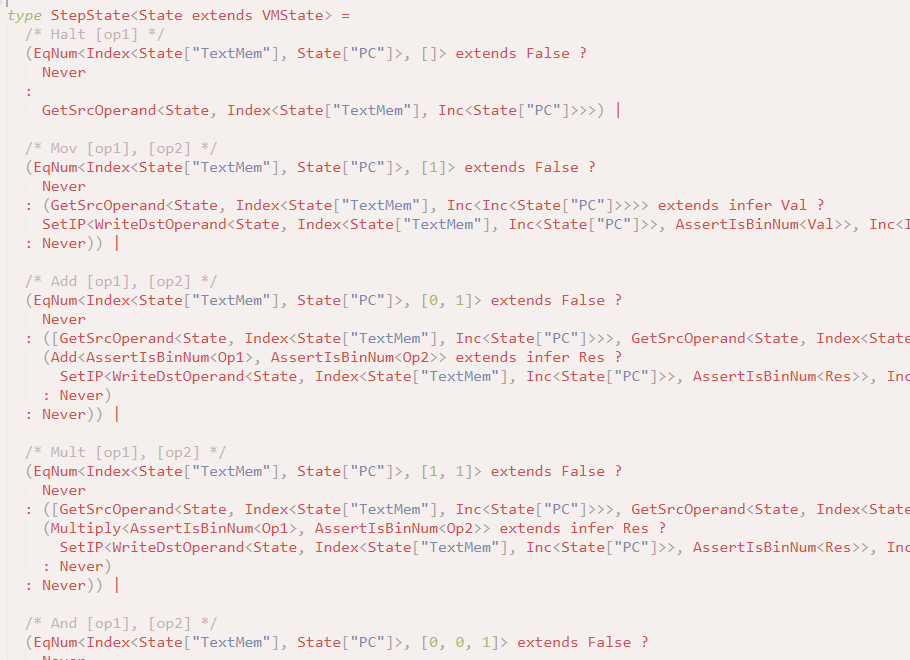

That’s right… a VM. Very quintessential reversing challenge stuff. It’s pretty satisfying actually. We started with bits, then we got gates, then an ALU, and now we have a CPU. It’s a pretty simple RISC architecture, here’s the processor state struct and the instruction set:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

type WriteHeaps<S extends VMState, x extends BinNum, y extends TNode | undefined> = {

"TextMem": S["TextMem"];

"PC": S["PC"];

"RegisterFile": S["RegisterFile"];

"Heaps": SetArr<S["Heaps"], x, y>;

"Stack": S["Stack"];

};

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

0x0 Halt [op1]

0x1 Mov [op1], [op2]

0x2 Add [op1], [op2]

0x3 Mult [op1], [op2]

0x4 And [op1], [op2]

0x5 Or [op1], [op2]

0x6 Xor [op1], [op2]

0x7 CmpSetne [op1], [op2]

0x8 Negate [op1], [op2

0x9 Jmp [op1] + pc + 2

0xa Jz [op1] + pc + 3, [op2 : flag]

0xb Heapadd [op1 : index], [op2 : key], [op3 : value]

0xc Heapremove [op1 : dstKey], [op2 : dstValue], [op3 : index]

0xd Mov16 [op1], [op2]

0xe Call

0xf Ret

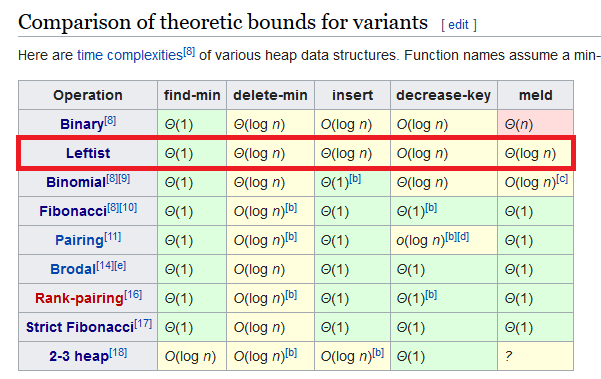

Right, so Tuna is an adder, and Swordfish is a register file…what? Anyways, one interesting thing is that there are instructions for manipulating a heap. I was really confused about the fancy heap implementation, so I ended up just looking at the table of popular heaps on Wikipedia.

…So I guess the challenge author decided that using an ordinary heap is too passe, so they had better spice it up by choosing the next one on the list, a fancy Leftist heap. We’ll discuss how these heap instructions are used later. For now, let’s actually focus on how our input gets used by this crazy VM:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

type Check_Input<Input extends Matrix> = StepStateUntilDone<InitializeVM<VMCode<Input>>> extends 0 ? Any : Never;

type WriteObj<Obj> = { -readonly [P in keyof Obj]: WriteObj<Obj[P]>; };

Main("your input goes here" as const);

function Main<Input>(input: Input & (WriteObj<Input> extends infer WInput ?

(WInput extends Matrix ?

Check_Input<WInput>

: Never)

: Never)) {

// decrypt flag

}

Essentially, this crazy VM is used as a type constraint on our input! Meaning, the type system, not the interpreted code, will check our input! It initializes a VM state using our input, then applies StepVM until the VM halts and returns a scalar. This scalar is the VM’s exit code (halt state) and is asserted to be zero. And that big array of binary digits we saw in the beginning is actually the VM’s bytecode. In any case, let’s dig into the VM, shall we? We wrote a disassembler, emulator, and debugger for the custom architecture and started reversing.

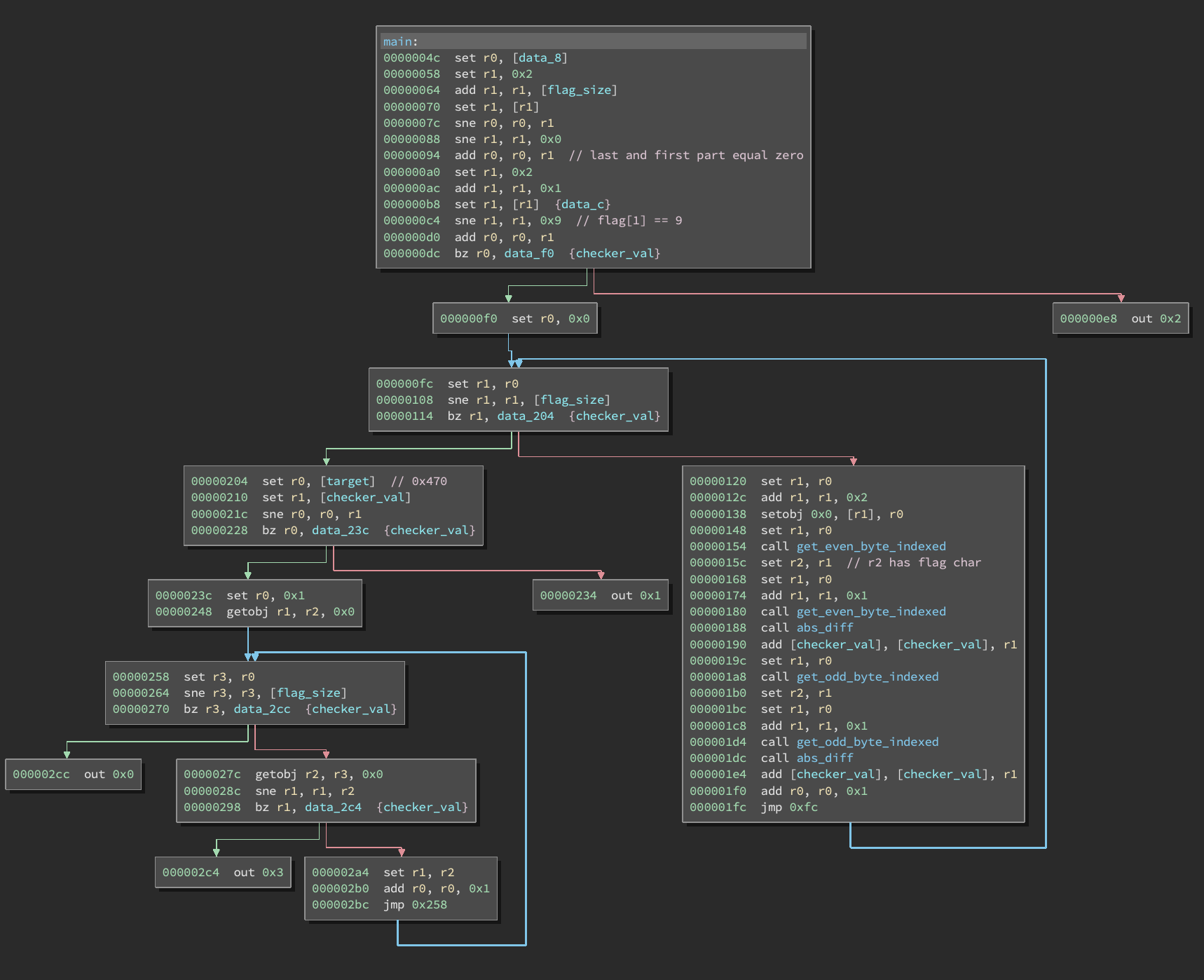

Here’s the control flow graph of the VM’s main function, from a Binary Ninja plugin Harrison Green wrote:

This is also where the heap comes in. It’s simply used to check that part of our input contains only distinct values. The code basically boils down to this snippet:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

xs = [0x09, 0xf0, 0xc1, 0xa9, 0xba, 0xc3, 0x8d, 0x80, 0xa1, 0x45, 0xd2, 0xf2, 0x03, 0xc8, 0x98, 0xb7]

ys = [0xda, 0xda, 0xee, 0xca, 0xd0, 0x89, 0x80, 0x5a, 0xc7, 0xf9, 0xa2, 0x43, 0x4f, 0x5a, 0x52, 0xfd]

# input is 17 hex digits. three values are hardcoded, rest are unknown.

inp = [0,9,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,x,0]

hash = 0

for i in range(16):

hash += abs(xs[inp[i + 1]] - xs[inp[i]])

hash += abs(ys[inp[i + 1]] - ys[inp[i]])

print(hex(hash))

assert(hash == 0x470)

assert(len(set(inp[:16])) == 16) # distinct

So, we’re essentially asked to find a permutation of (xs, ys) that results in the absolute differences of the consecutive elements summing to 0x470. This can be reframed as finding a Hamiltonian cycle of given length, where the metric is Manhattan distance! Luckily, we can use dynamic programming to solve this, but I’m not the best at algorithms. Thankfully sampriti saved me with his sick competitive programming skillz using bitmasks.

His solver gave [0,9,15,2,1,4,3,8,10,5,13,11,14,6,7,12,0], and this worked in our VM emulator too! The VM halted with code 0, which is correct. Now all we have to do is convert it to the input format the program wants, and run it!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

// Type constraints removed, cause its slow and runs out of memory lol

function main(input) {

let goldeen = input.map((x) => parseInt(x.join(""), 2).toString(16)).join("");

let stunfisk = "";

for (let i = 0; i < 1000000; i++) {

stunfisk = require("crypto").createHash("sha512").update(stunfisk).update(goldeen).digest("hex");

}

let feebas = Buffer.from(stunfisk, "hex");

let remoraid = Buffer.from("0ac503f1627b0c4f03be24bc38db102e39f13d40d33e8f87f1ff1a48f63a02541dc71d37edb35e8afe58f31d72510eafe042c06b33d2e037e8f93cd31cba07d7", "hex");

for (var i = 0; i < 64; i++) {

feebas[i] ^= remoraid[i];

}

console.log(feebas.toString("utf-8"));

}

main([[0, 0, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 1],

[1, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 0],

[1, 0, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 0, 0],

[0, 0, 0, 1],

[0, 1, 0, 1],

[1, 0, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 1, 1],

[1, 1, 0, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 1],

[0, 1, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 1, 0],

[0, 0, 1, 1],

[0, 0, 0, 0]])

// �PCTF{s0_Lon6_4Nd_tHanK5_f0R_4lL_Th3_f15H!_f74857d88a039}�

Whew. As someone who’s a fan of functional programming and lambda calculus, this was really rewarding! And also really frustrating. I’d gotten stuck for 10 hours, because I’d mistaken a VM opcode; luckily, theKidOfArcrania spotted my mistake. That’s what friends are for :) And, I also learned a lot of different types of fish.

You can find our fully-reversed code and solve scripts on our GitHub writeups repo. Also, if you like infosec memes, you can follow me on Twitter. Thanks for reading!